Stop the Chaos: How to Build an Effective Work Intake Process

Let’s talk about something that’s hiding in plain sight but derailing teams everywhere: how work comes to your teams. You know, that messy process where someone shows up at your desk saying, “I need you to build this thing,” or emails flood in with half-baked ideas, or executives drop “urgent” requests that completely derail your carefully planned product release.

Most teams are so focused on delivery methodologies—Scrum, Kanban, SAFe—they focus entirely on getting stuff delivered quickly. Having a bias towards speed is good, but here’s the thing: it doesn’t matter how fast your delivery process is if garbage is flowing in the front end [and I’m not talking about requirements]. Your intake model is the bouncer at the club, and right now, most organizations [and teams] have no bouncer at all. Or even worse, they have seven doors, with seven bouncers, that all have different takes on what to let in.

Why Intake Models Matter More Than You Think

Think about it this way: every piece of work that lands on your team started somewhere. Maybe it was a brilliant insight from a customer conversation, or perhaps it was someone’s pet project disguised as a “strategic initiative.” The difference between high-performing teams and everyone else often comes down to this simple question:

How are you managing everything coming at you to make sure it’s the most valuable thing to do?

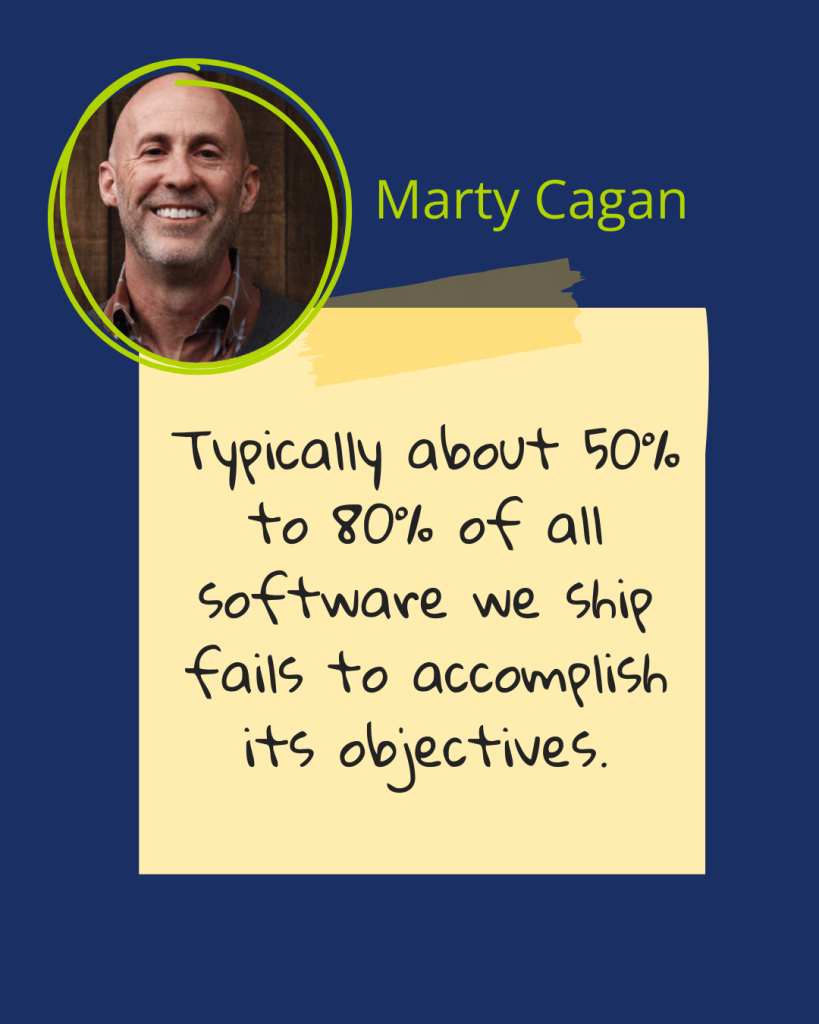

An effective intake process is likely the most impactful step that an organization [or team] can take, and here’s why. Without a clear intake model, teams get overwhelmed with requests, stakeholders get frustrated with a lack of visibility, and everyone loses sight of what actually creates value. You end up with the dreaded “feature factory”—lots of WIP, lots of output, zero outcomes.

But when you get intake right, magic happens. The organization and the teams have a focus. Stakeholders have an understanding of intent. Work flows smoothly from idea to delivery. And most importantly, you’re building things that actually matter. You won’t waste any of your heartbeats on stuff that people don’t care about.

Digging Into Three Intake Models

After working with many organizations and teams, I’ve seen many intake models, but there are three that encapsulate most — they can all work and fail, depending on the context and, of course, the people involved. Each has its place, and each can either supercharge your organization or completely derail it, depending on how you implement it.

Product-Oriented (a.k.a., Value-Stream Oriented)

This is the model where the Product Triad—Product Manager, Designer, and Engineering Lead—acts as the central nervous system for all incoming requests to a Product (a container of value with clear context, stakeholders, and customers/users). Everything flows through them, gets evaluated together, and either lands in the backlog or gets declined.

The awesomeness of this model is that requests get evaluated holistically. Whether it’s a strategic cross-cutting project, a brilliant new feature idea, continuous enhancements, or just fixing something that’s broken (see the aside)—it all gets looked at through the same lens: Does solving this provide value? Does this move us toward our product vision?

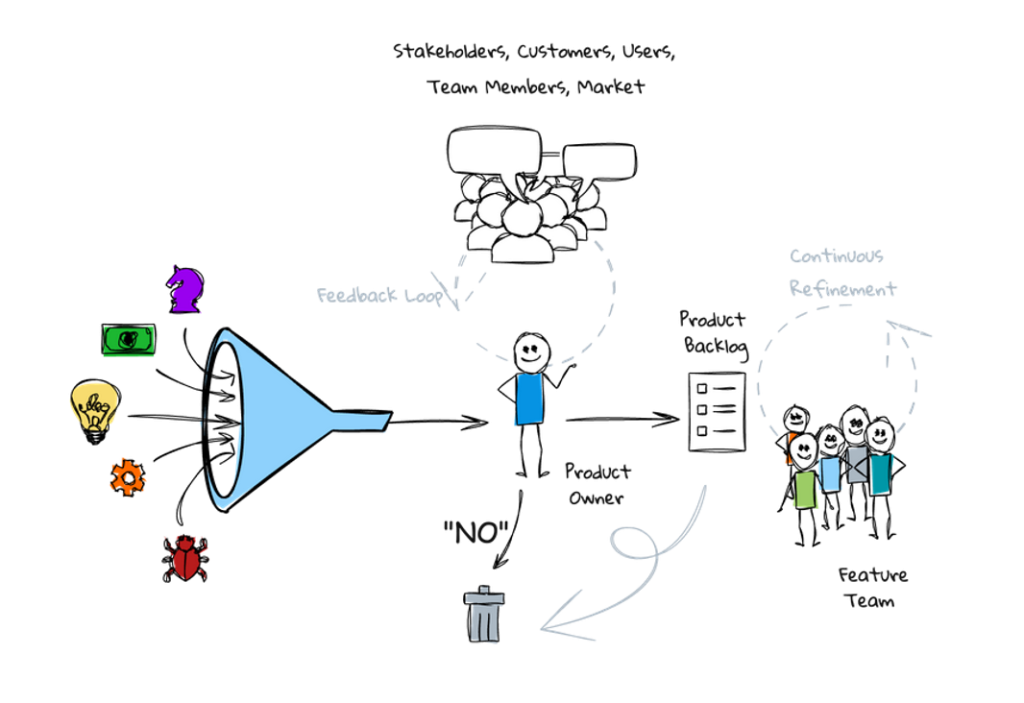

The Triad is constantly engaging with users, stakeholders, customers, and market experts. They’re gathering feedback, analyzing data, and making sure every request gets shaped into something that actually creates value. And here’s the critical part: they’re empowered to say “no.” In fact, saying “no” is their superpower to ensure the flow of value and information.

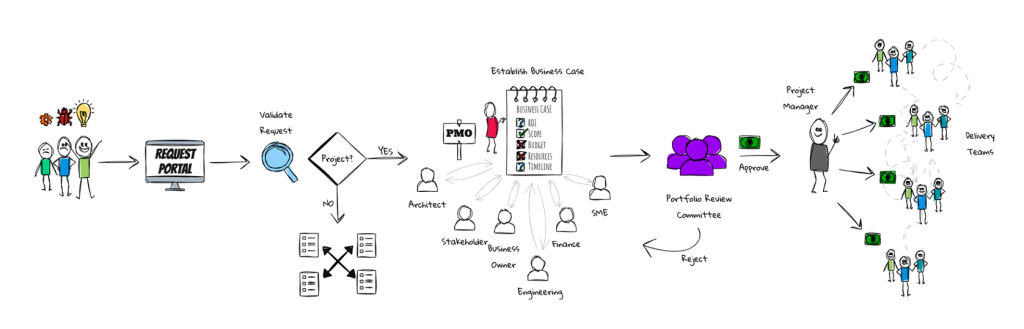

Project-Oriented

This is the traditional PMO approach, where requests endure a formal business case process before getting approved by a Portfolio Review Committee. It’s structured, it’s thorough, and it can work really well for organizations that need that level of governance. Especially if efforts are made to focus iteratively and incrementally, and all activities surrounding the process are passed through the Lean sieve.

With Project Oriented, requests come in through a central process, get validated for completeness, and if they qualify as a “project,” they move through a vetting process. The PMO helps flesh out business cases, multiple stakeholders provide input, and senior decision-makers ultimately approve or reject requests based on strategic alignment and resource availability [or a lot of horse trading].

Once approved, typically, a project manager carries the effort forward through delivery teams. It’s methodical, designed to drive accountability, and provides alignment with the portfolio.

Feature-Oriented

This is the lean and mean approach, where most requests flow directly to the Product Owner. The Product Owner is the single point of contact for problems, solutions, enhancement requests, bugs, and directives of “though must deliver my solution.” They’re in regular contact with stakeholders, customers, and users, and they have the authority to make quick decisions.

Keep-the-lights-on work goes straight to the backlog, while new capabilities might go through more discovery, definition, and validation. The Product Owner continuously refines the backlog, removing items that have been sitting idle for too long, and ensures the team stays focused on the most valuable features.

It can be fast, it can be flexible, and it puts decision-making power in the hands of someone who should be very close to the product and its users.

The Pitfalls, Tips, and Traps

Product-Oriented Pitfalls

The biggest trap with Product-Oriented intake is when the Triad becomes a bottleneck instead of an enabler. I’ve seen teams where the Triad meets once a week for three hours and becomes the organizational equivalent of the DMV [no offense to the DMV folk, you’re great!]—everything slows down to their pace.

Another common pitfall is when the Triad doesn’t actually have the authority they think they have. They say “no” to a request, and then three levels of escalation later, they’re being told to “make it happen anyway.” That destroys the entire model.

Pro tip: Make sure your Triad has real authority and that they’re meeting frequently enough to keep things moving. If requests are sitting for weeks waiting for Triad review, you’ve got a flow problem. The Triad should be constantly engaging, looking at things that are flowing through the system–Discovery through Delivery.

Project-Oriented Pitfalls

The classic Project Oriented trap is bureaucracy creep [or jerk]. What starts as a reasonable governance process becomes a six-month odyssey of forms, committees, and approvals. By the time you get approval to build something, the market has moved on or, in the case of regulated environments, the fines are stacking up.

I’ve also seen teams use this model to avoid making hard decisions. “Well, it went through the process” or “they told us to create the solution this way,” becomes the excuse for building something nobody actually wants.

Pro tip: Keep the process as lightweight as possible while still maintaining governance. And make sure your Portfolio Review Committee actually includes people who understand the product and the market, not just people who control budgets.

Feature-Oriented Pitfalls

The biggest danger with Feature Oriented intake is Product Owner [burnout|absence|incompetence]. When you’re the single point of contact for everything, you can quickly become overwhelmed. I’ve seen Product Owners who spend so much time managing requests that they don’t have time actually to own the product.

Another trap is the “small” enhancement iceberg. Without proper discovery, definition, and design processes, those “quick solutions” turn into major undertakings that derail your roadmap because the real problem to be solved was lurking below the water line.

Pro tip: Make sure your Product Owner has the support they need and clear criteria for what constitutes different types of requests. And don’t skip discovery just because something seems “small.”

When Each Model Works (and When It Fails)

Product-Oriented Works Best When:

- You have a product with a clear purpose, vision, mission, and a set of customers and users

- Cross-cutting concerns are common and co-exist with cross-cutting collaboration

- You need to balance strategic initiatives with operational needs

- Your team has the maturity to handle collaborative decision-making

It fails when: The Triad doesn’t have real authority, they become a bottleneck, or the organization is too immature to handle collaborative decision-making.

Project-Oriented Works Best When:

- You’re in an industry that requires formal governance [; otherwise, you might get called to the principal’s office]

- You’re dealing with large capital expenditures

- You have multiple funding sources that need clear accountability

- [The CEO is a PMP card carrier; therefore,] your organization has a strong PMO culture

It fails when: The process becomes more important than the outcome, decision-making becomes too slow, or teams lose sight of customer value while jumping through process hoops.

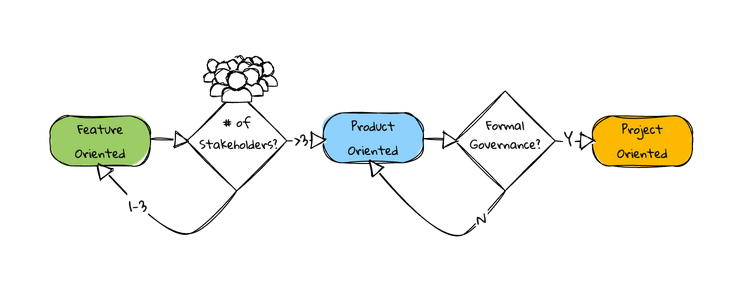

Feature-Oriented Works Best When:

- You have a dedicated feature team with a strong Product Owner

- You’re in a fast-moving market where speed matters

- Your product is relatively self-contained

- The product is mature and in the process of being exploited

- You have good relationships with stakeholders who trust the Product Owner

It fails when: The Product Owner becomes overwhelmed, stakeholders bypass the process, or the lack of formal governance creates chaos.

How to Choose the Right Model for Your Organization

The right intake model for your organization depends on five key factors:

Organizational Maturity: If you just read an article about agile, Product and Feature-Oriented, it might be too much autonomy too fast. If you’re adaptive and moving fast, Project Oriented might slow you down.

Regulatory Environment: Highly regulated industries often need the formal governance that Project Oriented provides. Whether an organization practices waterfall, agile, or a hybrid, projects are the containers for risk evaluation and management, so requests should be evaluated before work begins.

Stakeholder Complexity: The more stakeholders you have, the more you might benefit from Product Oriented’s collaborative, fast feedback loop approach. But if you have a clear hierarchy and simple relationships, Feature Oriented can work without the rigidity of Project Oriented.

Product Complexity: Cross-cutting products with lots of dependencies often need a product-oriented, project-oriented, or something in the middle intake approach. Simple, self-contained products can thrive with Feature-Oriented.

Cultural Preferences: Some organizations love themselves some process and governance (Project Oriented). Others prefer speed and autonomy (Feature Oriented). And those who bleed customer centricity (Product Oriented). Fighting your culture is usually a losing battle.

Here’s a simple decision tree: Start with Feature Oriented if you’re a single product team with good stakeholder and customer relationships. Move to Product-Oriented when you have multiple stakeholders and complex decisions. Only go Project Oriented if you absolutely need the formal governance.

The In-Between: Hybrid Models That Actually Work

The dirty secret about intake models is that most successful organizations don’t use just one. They develop hybrid approaches tailored to their specific context.

For example, you might use Feature Oriented for day-to-day enhancements and bugs, Product Oriented for new features and strategic initiatives, and Project Oriented for significant capital expenditures. The key is being explicit about which model applies to which type of request.

Teams can be held responsible for their own work intake, provided they follow established processes that include regular touchpoints at the portfolio level. This gives teams autonomy while maintaining strategic alignment.

Another common hybrid is using different models for different teams within the same organization. Your core product team might use Product-Oriented intake, while your platform team uses Feature-Oriented, and your compliance team uses Project-Oriented. As long as everyone knows which model applies to them, it can work beautifully.

The traffic light system is particularly effective for hybrid models: Green means the work item can move forward, Amber means more thought is needed, and Red means serious reconsideration is required. This provides clear guidance while allowing flexibility in how different types of work get evaluated.

The Gotchas: For each of these approaches, decisions are made around what gets started and the prioritization of work. In each of the intake approaches, teams may have their own #1 that conflicts with the big picture, and you'll see teams starting a lot of work due to project-required milestones or the ever-changing feature prioritization. In both cases, we are talking about too much organizational work in progress (WIP) and a misalignment in priorities that typically leads to integration challenges (a.k.a., integration hell).

To overcome these gotchas, ensure channels are clear, all work is visible together, and conduct frequent alignment sessions across project and product portfolios that look at objectives to ensure everyone is clear on what is most valuable for the organization.

Making It Work: The Implementation Reality Check

Here’s the thing about intake models: they’re not just processes, they’re cultural changes. And cultural changes are hard.

The biggest mistake I see organizations make is focusing on the mechanics—the forms, the tools, the meetings—without addressing the underlying behaviors and deeply rooted habits. You can have the most beautiful intake process in the world, but if stakeholders are still walking up to their favorite developer or Tech Lead and saying, “Can you just quickly…” then you don’t really have an effective intake process.

Start with the “why”: Before you implement any intake model, make sure everyone understands why it matters. Too little information can result in work being approved that doesn’t align with strategy, exceeds financial, capacity, or other constraints, or doesn’t provide solid value. Help people see how the current chaos is hurting them.

Find your process champion: You need someone who’s going to hold everyone accountable to the new process. This is the person who is going to physically get up and walk into every single person’s office, hold their hand, and show them how to use the intake process correctly, and then insist they do it that way every single time. They educate, influence, and walk the talk–and they are given the time to do so.

Hold firm on boundaries: If people can still bypass your intake process, then you don’t have an intake process. You have a suggestion. Be willing to say, “I can’t work on this because I don’t see it in our system.” Try to create a process that meets the “Simplicity — the art of maximizing work not done — is essential” principle and doesn’t have a single exception [or workaround].

Iterate and improve: Like any process, your intake model will need refinement. Getting the intake management process right takes time, and it’s likely you’ll go through several iterations before you find exactly the right configuration and cadence for your organization. Be okay with not perfect, and adapt. Be sure to measure flow and downstream impacts.

The Bottom Line

Your intake model is the difference between being a reactive team that gets jerked around by every urgent request and being a strategic team that delivers real value. It’s the difference between building features and building products. It’s the difference between keeping stakeholders happy in the moment and actually moving your business forward.

Many teams spend months optimizing their delivery process while completely ignoring their intake process. Don’t be one of those teams. Get your front door right, and everything else becomes easier.

Remember: the goal isn’t to create more process—it’s to create better outcomes. Choose the intake model that fits your context, implement it with conviction, and be willing to evolve it as you learn.

Because at the end of the day, the teams that win aren’t necessarily the ones that deliver the fastest or most predictably. They’re the ones that consistently deliver the right things. And that starts with how work gets in the door.